Charting a Safer Course for DRI Fines

INTRODUCTION

The 3Q2021 edition of DFM included my article, “The IMSBC Code: Regulatory framework for international shipment of solid bulk cargoes,” which first of all provided background information about the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) and the International Maritime Solid Bulk Cargoes Code (IMSBC Code) and then explained the IMSBC Code’s relevance to the various forms of DRI:

- Direct Reduced Iron (A) Briquettes, hot-moulded

- Direct Reduced Iron (B) Lumps, pellets, cold-moulded briquettes

- Direct Reduced Iron (C) By-product fines

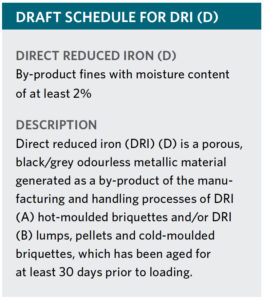

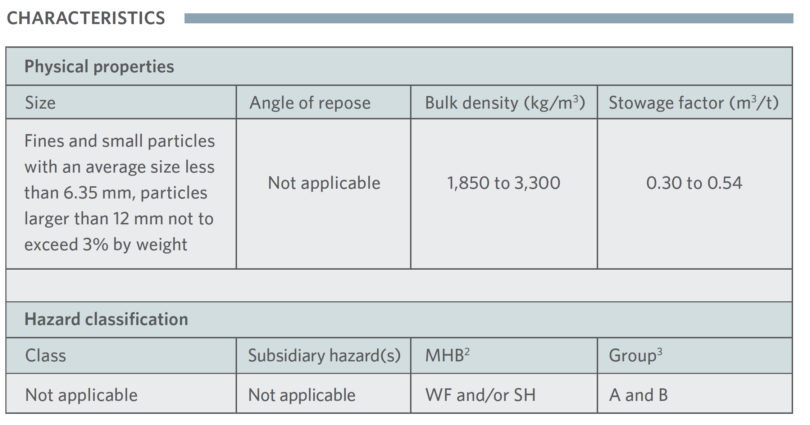

Of the three forms of DRI, DRI Fines have been the most actively discussed in recent years, currently included in the IMSBC Code only by the largely unrepresentative schedule for DRI (C). Therefore, this article will present the current state of this discussion and the solution that has been accepted in principle, i.e. the proposed schedule for DRI (D) (By-product fines with moisture at least 2%), which will provide a mandatory legal instrument governing international maritime shipment of DRI Fines and ensure shipment in the safest manner possible.

CURRENT IMSBC CODE DRI (C) SCHEDULE

DRI (C): A porous, black/grey metallic material generated as a by-product of the manufacturing and handling processes of DRI (A) and/or DRI (B). The density of DRI (C) is less than 5,000 kg/m3. A loading requirement for DRI (C) is that the moisture content shall not exceed 0.3%.

Hazard: Temporary increase in temperature of about 30o C due to self-heating may be expected after material handling in bulk. There is a risk of overheating, fire and explosion during transport. This cargo reacts with air and with fresh water or seawater to produce hydrogen and heat. Hydrogen is a flammable gas that can form an explosive mixture when mixed with air in concentrations above 4% by volume. Cargo heating may generate very high temperatures that are sufficient to lead to self-heating, auto-ignition, and explosion. Oxygen in cargo spaces and in enclosed adjacent spaces may be depleted. Flammable gas may also build up in these spaces. All precautions shall be taken when entering cargo and enclosed adjacent spaces. The reactivity of this cargo is extremely difficult to assess due to the nature of the material that can be included in the category. A worst-case scenario should therefore be assumed at all times.

ONGOING DEBATE OVER DRI FINES

With respect to DRI Fines, it is important to note that the vast majority of shipments of this material contain moisture content greater than the maximum 0.3% required for carriage of DRI (C), typically 5-6%, but less than the Transportable Moisture Limit, (TML ). For such material, the principal hazard is evolution of hydrogen rather than self-heating. Therefore, shipments have for many years and continue to be covered by exemptions in accordance with Section 1.5 of the IMSBC Code which permit the higher moisture content and require mechanical surface ventilation as the principal measure for dealing with the hydro-gen hazard, a practice safely employed by the industry for many years.

The debate at the IMO about DRI Fines dates back to 2006, and despite attempts by the industry to introduce a schedule for DRI Fines with moisture content higher that 0.3%, the deci-sion of the then Sub-Committee on Dangerous Goods, Solid Car-goes & Containers (DSC, now the Sub-Committee on Carriage of Cargoes and Containers [CCC]) was that DRI Fines should be treated in the same manner as DRI (B). Hence, the DRI (C) schedule was adopted with self-heating as the principal hazard and inerting cargo holds, usually with nitrogen, as the principal mitigation measure.

For the last 10 years or so, further attempts have been made at the IMO to introduce a new IMSBC Code schedule for DRI Fines with higher moisture, embodying mechanical surface ventilation as the principal mitigation measure. Concerns about the effectiveness of ventilation have been raised, as underlying this process are long memories of past incidents with DRI Fines, notably the tragic loss in 2004 of six lives and the M/V Ythan, a bulk carrier enroute from Venezuela to Asia with a full cargo of DRI Fines.

For the last 10 years or so, further attempts have been made at the IMO to introduce a new IMSBC Code schedule for DRI Fines with higher moisture, embodying mechanical surface ventilation as the principal mitigation measure. Concerns about the effectiveness of ventilation have been raised, as underlying this process are long memories of past incidents with DRI Fines, notably the tragic loss in 2004 of six lives and the M/V Ythan, a bulk carrier enroute from Venezuela to Asia with a full cargo of DRI Fines.

Industry, working collaboratively through IIMA since 2014, has co-operated with key national IMO delegations and affiliated NGOs (non-governmental organizations) in trying to find a workable solution, culminating in an agreement in principle in March 2022 to an updated draft schedule, designated DRI (D). This new schedule will be included as part of Amendment 07-23 to the IMSBC Code, which was referred to CCC and, in turn, to the subsequent E&T (Editorial & Technical Group) meeting for finalization. It is gratifying that the DRI (D) schedule survived this process intact and amendment 07-23 will be referred to the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) for final approval.

Amendment 07-23 including the DRI (D) schedule, will become mandatory from 2025.

The basics of the schedule have not changed significantly during the process; i.e., the principal hazard being evolution of hydrogen, with the principal mitigation measure being mechanical surface ventilation. However, in order to move it forward, a number of generally value-added changes and modifications were introduced, the most significant of which are described below (the entire draft schedule runs 11 pages and can be downloaded from IIMA’s website https://www.metallics.org/logistics-guides.html.

INTRODUCTION OF MINIMUM MOISTURE CONTENT OF 2%

Behind this development was the premise that moisture contained in DRI Fines has an inhibiting effect on self-heating (as described in a paper submitted to DSC by IIMA , entitled “The effect of the seawater on DRI (C) hydrogen gas generation and on the self-heating of this cargo,” based on experimental work in Venezuela). This premise occupied more than a little time at subsequent CCC/E&T meetings.

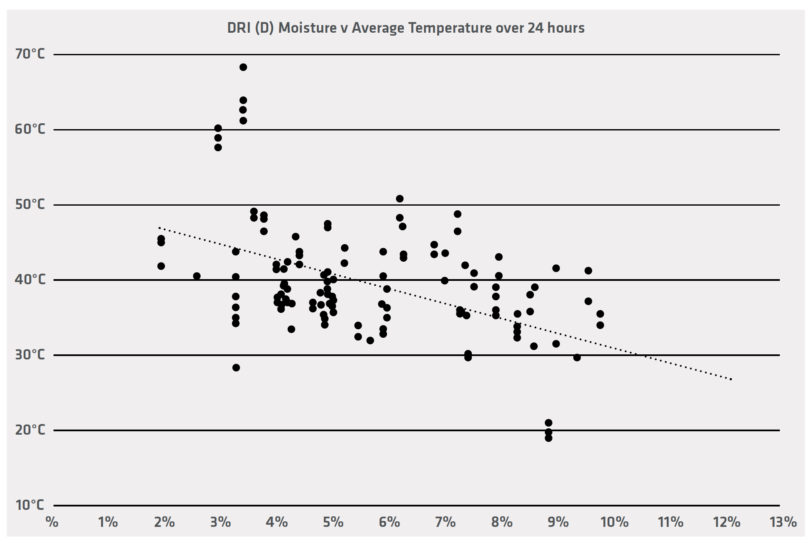

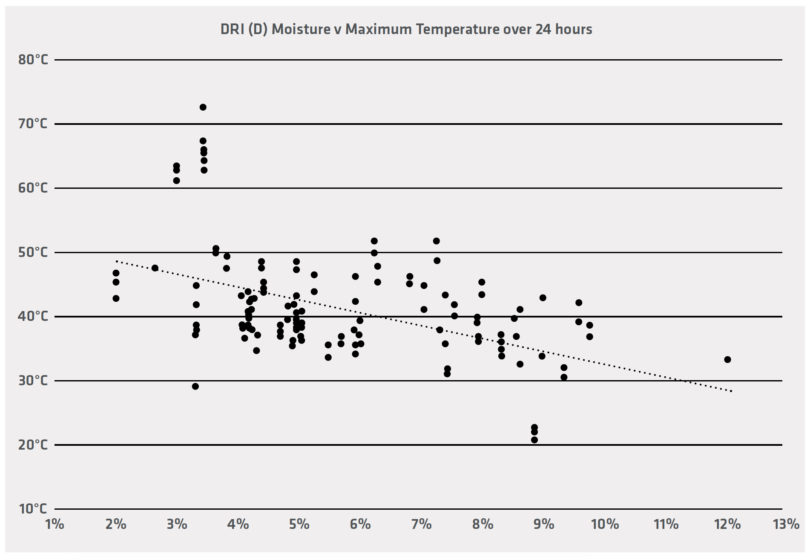

IIMA analysed a data base of actual shipments made between October 2016 and September 2018, which included:

- shipments totalling 1.085 million tons of DRI Fines

- moisture contents ranging from 2.0% up to 12.1%

- temperature measurements in 134 holds during 47 voyages on 18 different vessels

- average voyage length of 16 days (range 8 to 42 days)

- origins including Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago, US, and Egypt

The results of this analysis with the following charts were presented to CCC in July 2020 with the following conclusions:

- There is a relationship between temperature and moisture content with a reduction in temperature as the moisture content increases.

- The analysis supports the proposed minimum moisture content of 2%.

REQUIREMENT FOR CERTIFICATION THAT THE CARGO DOES NOT MEET THE CRITERIA FOR CLASS 4.2 MATERIALS

The draft schedule requires this certificate to be provided by a competent per-son to the master of the vessel prior to loading a cargo. A class 4.2 material falls under the description “dangerous goods,” Class 4.2 being a substance liable to spontaneous combustion (materials, other than pyrophoric materials, which in contact with air, without energy supply, are liable to self-heating). DRI (D) as currently shipped is not Class 4.2 (the relevant test being N-4 from the UN Manual of Tests and Criteria, Part III, Section 33.4.6)6.

This addition to the draft schedule was a compromise with several member states whose concern was that, whilst the DRI (D) schedule is appropriate for DRI Fines as currently shipped, the material properties might change in the future such that the material becomes Class 4.2.

Shippers will need to find a practical, non-onerous means of providing the required certification.

ASPECTS OF DRI (D) SCHEDULE

Cargo Technician

It has been standard practice and in-deed a requirement of exemptions to the IMSBC Code that an experienced cargo technician be on board the vessel during loading and throughout the voyage in order to assist with cargo monitoring and to provide advice as needed by the master of the vessel and crew. The mandatory requirement for a cargo technician was strongly opposed by some for various reasons and in the end, it was agreed that it would be recommendatory rather than mandatory.

IIMA regrets this development, which in effect is a compromise in the interest of progressing the draft schedule, and still strongly supports the appointment of a cargo technician. In the absence of appointment of a cargo technician, the master or a designated representative shall seek advice from the shipper or other competent person.

Risk assessment

Prior to loading, the shipper shall provide the master of the vessel with comprehensive information about the risk of hydrogen evolution and the factors which affect the rate thereof. This risk assessment may include expected weather conditions, available information on the rate of hydrogen evolution for the cargo in question, vessel speed, availability and accessibility of ports of refuge enroute, and distance to the port of discharge.

The risk assessment, voyage plan, and weather routing, if adopted, shall be updated frequently during the voyage as updates on the weather, as well as actual hydrogen evolution rates, become available.

Ventilation requirements

The updated schedule requires that in order to minimize the possibility of the introduction of oxygen and moisture into the cargo holds, periods of surface ventilation shall be limited to the time necessary to remove hydrogen which may have accumulated in the cargo holds and to maintain the hydrogen concentration below 1% by volume (25% of the lower explosive limit, LEL). Previously, continuous mechanical ventilation was required. The operating period and frequency of the ventilation system shall be determined based on the measured hydrogen concentration and the indicated rate of increase/ decrease thereof over time. Therefore, it is very important to establish a time-based gas prediction curve. Such curve shall be first determined prior to sailing and, recognizing that conditions can change, updated from time to time during the voyage as may be appropriate, for example in the case of seawater intrusion into a hold carrying this cargo.

In order to develop such a curve, a cargo hold shall be ventilated until the hydrogen concentration falls to or below 0.2% by volume (5% LEL), then ventilation (both natural and mechanical) to such hold shall be stopped, and the hydrogen concentration measured every 2 hours thereafter for at least 24 hours or until it reaches 1% by volume, whichever occurs first. If the concentration reaches or exceeds 1% by volume, the respective cargo holds shall be ventilated and measurements continued to ensure that the concentration of hydrogen has stabilized and remains sustainably at or below 0.2% by volume (5% LEL).

CONCLUSION

With one more step to go in the IMO process, i.e., approval of amendment 07-23 to the IMSBC Code by the Maritime Safety Committee at its 107th meeting in June 2023, this particular task is nearing its conclusion. In 2025 the amendment will become mandatory (with voluntary adoption from 2024) and as such will (a) provide a global legal instrument governing maritime shipment of DRI Fines with at least 2% moisture and (b) obviate the need for exemptions. IIMA has long championed the need for such a mandatory instrument and the need for global compliance – the industry can ill afford the reputational damage that would result from another unfortunate incident.

The DRI (C) schedule will remain in the IMSBC Code in order to provide a basis for the very rare shipments of DRI Fines with moisture content of up to 0.3%.

The question then arises about how to deal with DRI Fines with moisture content above 0.3% and less than 2%. The short answer to this is that maritime transport of such material will not be legal without an exemption and should better be dealt with by producers through improved in-plant storage measures, etc.

Whilst recycling of DRI Fines by the producer is an ideal solution, this is not always an economic proposition and maritime shipment will certainly continue and even grow as production of DRI increases along the pathway to decarbonization of steel production.

I would like to acknowledge the enormous contribution of IIMA’s DRI Fines team, comprised of DRI producers, shippers, cargo technicians, and other experts, shipping companies, etc. I also want to acknowledge with grateful thanks the assistance, advice, and co-sponsorship of the DRI (D) schedule from Belgium, Canada, the United States, and the NGOs – BIMCO, ICS, Intercargo, and the International Group of P&I Clubs.

Author’s note (cbarrington@metallics.org)